I don’t love slasher films because I’m a gorehound – quite the opposite in fact. I love them because I like to see people survive against the odds, because I love it when a ‘weak’ opponent manages to find in themself the strength and ferocity to turn the tables on their attacker.

I’ve been meaning to write about this topic for a while now and, after reading some academic film theory of late (plus struggling with non-review ideas for the site), thought I may as well just go for it.

Way back in 1997 when I started my film degree, there was almost nothing to read on slasher films. Games of Terror and Men, Women & Chain Saws were it, both academic texts, both well written, both by female critics.

This last point matters because both texts erred towards the implication carried over into the mere mention of the sub-genre in other books as ‘women-hating’, ‘anti-feminist’, and ‘misogynistic’.

The common assumption of how any slasher film goes down: Young women menaced by a phallic weapon at the hands of a male aggressor.

Games of Terror is about the formula far above and beyond gender ins and outs, but touches on it occasionally. In Men, Women & Chain Saws (hereafter MWC) Carol Clover pretty much tells porkies to illustrate her point, beginning with a meta-description of a slasher film that says a killer picks off ‘mostly female victims’, before using a bunch of films for reference where male victims outnumber females. Duh.

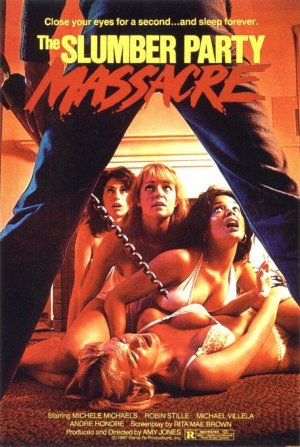

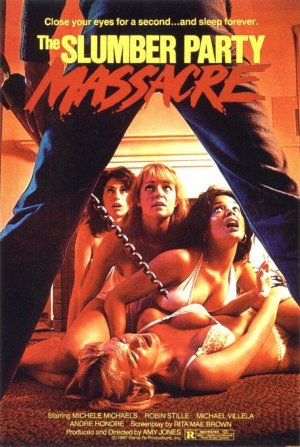

Still, numbers aren’t everything. The main point made in MWC is that terror is ‘gendered feminine’ and that can’t really be denied. Think back to almost every piece of slasher movie artwork commissioned, be it a quad poster, VHS cover, or DVD redesign, the recurrent theme is of a babe in peril, sometimes only partially dressed, often screaming as a shadow/blade/pair of straddled legs threaten her.

Various girls-in-peril artwork, often featuring a phallic penetrative blade at the hands of a male aggressor.

This is evidenced in the mention of slasher films in other entertainment: In an episode of Will & Grace, a male character proclaims he feels “like a sorority girl in a bad slasher film”; in Sister Sister, girls at a slumber party watch a movie and narrate: “Freddy’s going after the girl.” A character in Dawson’s Creek refers to slasher films as being nothing but “masked men slashing up girls.” The popular myth of the genre appears to be that the slasher film is almost entirely about the torture of teenage girls.

The films lean heavily on the prolonged torment of their female characters – from the ‘quick scream and chop’ murders, the long chases down dark halls or alleys, to the final girl’s initial reluctance to fight back. To pin it down – how often do we see male characters tormented in the same way?

A large majority of slasher films are about a killer chasing girls, who happens to kill boys who get in the way: Sorority House Massacre, for example, is an exercise in babes in peril: The killer wants only to kill girls who resemble (to him) his sisters, the male victims (who incidentally outnumber females 5 to 3) just happen to cross his path and must be eliminated.

Boys scream and flee too

My argument would be that the expanded terror afforded to teenage girls in slasher films is in part ‘made equal’ by the greater number of male victims over all. 697 films in, male fatalities outnumber the fairer sex 61% against 39% with only 20.5% of films featuring more murdered women than men.

I raised this on a blog to which the author responded with a surly comment that the fact men ‘also’ die doesn’t detract from the misogyny at work and that slasher films serve to play to male fantasies of women being cut up. If so, why have male victims at all, let alone more male victims? I don’t for a second believe that Terror Train‘s singular off-screen female homicide out of TEN murders plays into any such nonsense, same goes for Happy Birthday to Me, and the two-vs-six body count in Hell Night. Do dead men matter less?

The point was compacted by the fact that in her essay, the writer didn’t namecheck or reference a single post-Halloween slasher film. Not one. Dressed to Kill, some 70s proto-slashers, and giallo films do not your point make. If I’d handed in an academic essay on film without citations, no matter how well written, I’d have failed. It’s baseless, anecdotal at best.

That said, critics would often state that the way in which women – particularly attractive teenage girls – are killed tips the balance. Despite box office receipts for Halloween and Friday the 13th showing 55% of under-17s were girls, most teen-horror is still written, produced, and directed by straight men, and thus the inextricable link between slasher films and T&A has never died out – look no further than IMDb boards for hordes of complaints when a slasher film doesn’t feature any nudity.

Clover made a point of stating that boys die because they make mistakes, whereas girls are murdered because they are girls. While this might resonate in low-end exploitation films where the killer targets only females and a male happens to get in his way, early plot-driven slasher films heavily leant on mystery angles where the killer targeted a specific group of young people, always mixed gender. The boys in Terror Train die because of their prank against the killer; boys in Friday the 13th are doomed as much as their girlfriends because the killer is hellbent on obliterating them all; same goes for Graduation Day, Hell Night, My Bloody Valentine… Errors in what dark room they should or shouldn’t enter aside, nobody in these films is killed ‘because of their gender’.

The boys and girls of Camp Crystal Lake: Equal opportunity doom

The sequences leading up to the murder of a female character is usually more drawn out than that of her male friends. One might say that the quick from-behind hijacking of boys in slasher films is to prevent a physical retaliation less likely to occur when a girl is stalked. This could also feed into the lack of instances across the board of a male in terror: ‘Weak’ men scream (see Trent in the Friday reboot) and run away; ‘real’ men stay and fight (see Julius in Jason Takes Manhattan) even if they almost always fail. The myth that is upheld is that when it comes to fight or flight, men will choose the former, women the latter.

Taking the Friday films as an example, in the oft-seen sequence where a couple’s sex is interrupted, most of the time the boy will leave the girl to get ice/beer/investigate a noise, and be killed first, usually quickly. This leaves the girl alone in the house/cabin with the killer, the scene slows down, the photography fragments, framing her from a variety of angles to confuse the viewer into wondering where he will pounce from, while she takes a shower, calls out for the boy, or flees having stumbled across his body.

In the 2009 remake of My Bloody Valentine, this was cranked up in a scene where the male half of a recent tryst dresses and leaves, while the woman follows him, completely naked, and is then pursued by the killer after the man is suddenly offed with a pickaxe. His death is swift, over in a second, while she is subjected to being accosted, stark naked, screaming, hiding, and hopelessly trying to defend herself.

It’s worth noting though that fellow 2009 slasher, Tormented largely reversed this scenario, with a buff guy in partially-on boxer shorts, runs across a school campus from his killer.

Naked, tormented victim in My Bloody Valentine (2009)

Then there are the films where female characters are punished for ‘sins’ that pale in comparison to those of their male contemporaries, who are spared: Valentine begins with three girls refusing to dance with a dorky boy, while a fourth accuses him of attacking her so that a group of boys pour punch over him, strip him to his underwear and kick the crap out of him. Years later, the girls are stalked and slashed, the boys seemingly forgotten. The same thing applies in My Super Psycho Sweet 16, where several jocks beat up the dorky friend of the heroine, but only the ringleader is killed, whereas the female friends of the bitchy girl are beyond redemption, even when one of them expresses remorse for the way they’ve treated the final girl, and all are summarily murdered.

In Girls Nite Out cheerleaders on a scavenger hunt are slashed by a killer who roars “Slut! Bitch! Whore!” while a roster of extremely annoying frat boys, the nominal hero of whom cheats on his girlfriend, escape the blades. That the killer turns out to be female may be a half-hearted effort to side-step the misogyny in play as a woman judging the promiscuity of other women rather than a man. The Prowler is another early film where the killer targets girls, after his ego is bruised by being dumped 35 years earlier. The three male victims (out of seven) killed are either attacked from behind without even seeing the killer or shot out of the blue. The Burning sees a group of boys roast a caretaker almost to death, yet when he returns for revenge several years later, his victims are primarily female.

Few films have tried to flip this trend: The Slumber Party Massacre may have been meddled with during production, but aspects of the initial missive come through – the boys die quickly, shrieking and thrashing as they’re stabbed or drilled, while the girls pool their resources and strike back with ferocity, figuratively castrating the killer by lopping the end of his phallic drill-bit, playing up to the notion that the male killers are impotent men incapable of sexually pleasing a partner, so opting to stab her over and over with a phallic weapon in a grotesque perversion of the sexual act.

The ending of The Slumber Party Massacre is an excellent celebration of oestrogenic fury as the trio of final girls retaliate, and still the film was eventually pushed out with a ‘traditional’ emphasis on the babes-in-peril angle:

Equating violence with sex doesn’t come much more obvious than that.

Later on in the cycle, the tropes began to be parodied. In Cut (2000) the tyrannical (female) director yells at the actor playing the killer for forgetting to cut open a victim’s blouse before slashing her throat; the slasher film being made in Brian De Palma’s Blow Out is also run by a producer who wants girls for “tits and a scream”.

The Scream movies have often been cited for portrayals of strong women. However, it’s worth noting that in those movies, the stalking element is exclusively geared towards girls – the Halliwell Film Guide even summarised the plot of the original as “a killer is murdering girls” in spite of the fact that more males die. In each Scream however, the opening scene shows a young woman (or women) being tormented by the killer. Her male companion is usually killed off quickly. The third film flipped it and the male character’s death was more protracted, and the fourth opted for a clever joke of an opening with two fake-outs before the real double-murder, ultimately amassing five deaths of young women. This is a series that may push Sidney Prescott and Gale Weathers to pound on their male aggressors, but is pivoted by men who are always attacked either from behind or with no time to act, and girls who run and scream before they’re killed.

Double final girl power in Scream 2, offsetting the prolonged torment of other female victims in the series

More recently, in the 2015 indie pic Bastard, all relevant roles are taken by women: The killer, final girl, and her would-be saviour. This is a film where the only on-screen murders are of men.

Conclusively, there’s no way to call it. There are exceptions to every rule the slasher universe has ever thrown out: Protracted male chase scenes occur in Mask Maker and I’ll Always Know What You Did Last Summer, but they lack the fear on behalf of the viewer for the fate of the victim. Do we care more about the girls than the boys? Read a few IMDb boards and you’d think anything but.

The back and forth could go on and on, but given that the slasher realm offers meaty leading roles for women, I’d say that trumps most accusations of misogyny. It’s got to be far more empowering to watch Jamie Lee Curtis, Amy Steel, Heather Langenkamp, or Neve Campbell fight off a killer with ferocious gusto than see them playing the wife or girlfriend of a guy who has all the adventures in any other genre.

Personally, a slasher film without screaming girls running about is usually a bad one, but I tend to get tetchy when the motif is repeated more than once per film, or when asshole guys are given a free pass while their much nicer girlfriends are brutally slain (see Honeymoon Horror, Berserker, even the recent Most Likely to Die). The best genre examples levelled it out: Kill some boys, kill some girls, but always leave one girl to save the day.

So are they misogynistic? I’d say largely – intentionally – no, but some certainly have their moments.